If you are experiencing the juvenile court system for the first time, you likely have many questions about the process itself. One of the most frequently asked questions we receive from both parents and children is: when is a child detained? The answer relies upon a tool used by juvenile courts in Georgia called a “Detention Assessment Instrument,” or “DAI” for short.

The Detention Assessment Instrument “DAI”

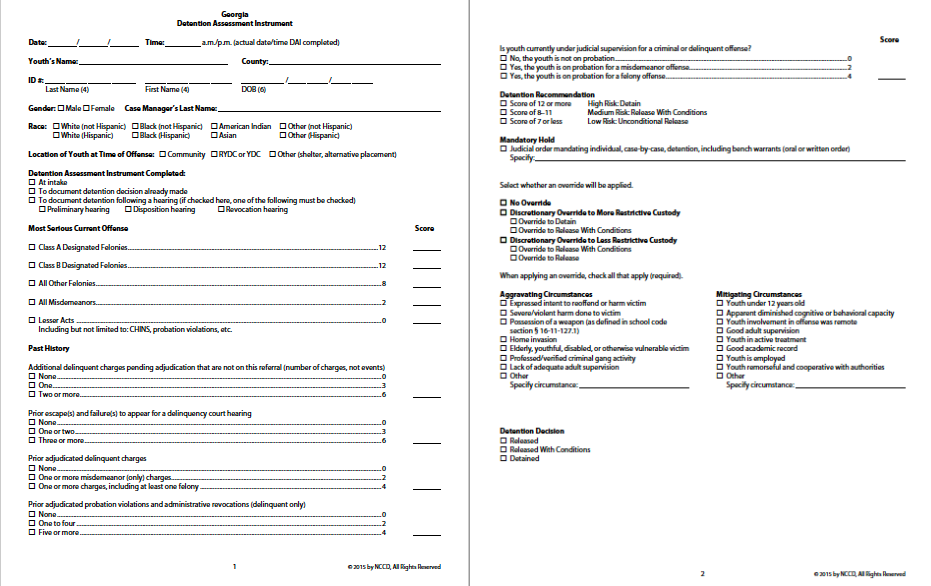

When a child is arrested, Georgia law requires a juvenile court intake officer to administer a DAI to determine whether a child will be detained or released to their parents. The DAI takes into consideration factors such as the level of offense of which the child is currently accused, other offenses the child is alleged to have committed or has been found to have committed (adjudicated delinquent), whether a child has failed to appear for a previous court hearing, and other similar factors. The responses to these questions are assigned points and tallied up to determine a child’s “risk level” for the purposes of a detention decision. An example of a DAI is included below:

The three risk categories on DAIs in Georgia are typically 1) low risk (unconditional release), 2) medium risk (release with conditions) and 3) high risk (detain). While the tallied points generally guide the detention decision, the juvenile intake officer can override the DAI if aggravating or mitigating circumstances are specified. Some examples of aggravating circumstances are the level of harm done to the alleged victim, whether a weapon was involved, and whether the alleged victim was a vulnerable person (such as elderly or disabled). Examples of circumstances that could mitigate a decision to detain a child include whether the child was under the age of 12, academic record, employment, and expressions of remorse.

A police officer might say that they “did not have enough points” to detain a child. What that means is that a juvenile intake officer conducted a DAI and found the child to be low risk. Absent the aggravating circumstances mentioned above, regional youth detention centers (RYDCs) will not accept a child for detention that does not meet the DAI criteria for detention. In these cases, the child is released into the custody of their parents.

The Problem with Risk Assessment in the DAI Process

The problem with risk assessments is the same problem that the juvenile court system faces in most areas: racial bias. Research has found that risk assessments are more likely to misclassify youth of color as high risk relative to their white peers. There are issues with the way “risk” is calculated, the domains and items included in the risk assessment itself, and failure to adjust weights and/or shift cut-off points make the tool more likely to misclassify children of color.

“Risk” as previously mentioned typically means the probability that a child will reoffend in the future. The way bias is injected into this analysis is that it measures the juvenile court system’s response to that child, as opposed to the behavior of the child themselves. Offending is measured by re-arrests, technical violations, and reconvictions as proxies for offending. Research has shown that youth of color, specifically Black youth, are more likely than their white peers to be arrested, have their case referred to the juvenile court (as opposed to diversion programs), and to be placed in detention. This is but one way that racial bias is injected into the DAI analysis.

Another way that racial bias permeates the DAI is in the domains and items related to a child’s juvenile court history (for example, previous involvement with the court system, first age of involvement with the court system, whether a child has been incarcerated previously). If police are more likely to arrest children of color, then using age of first arrest (or number of previous arrests) will disproportionately affect children of color. Even domains such as education, that seem equitable on their face, can be subject to racial bias. Questions as to whether a child has been suspended or expelled from school can be of issue because of the research that shows that children of color, specifically Black children, are suspended and expelled from school at rates disproportionately higher than their white peers.

DAI Process Does Not Ensure Equity in Detention Decisions

Due to the issues with bias previously mentioned, there are issues with how the DAI score is weighted. Without the ability to adjust for the inherent racial bias in the process the DAI will continue to misclassify youth of color as high risk disproportionately to their white peers. Research has demonstrated that when the domain of previous involvement in the juvenile court system is weighted to have a less significant impact on the overall risk score that the odds of children of color ending up in the higher risk score decrease.

As you can see, DAI scores do not produce the equity in detention decisions that the very purpose of the process sets out to establish. There are also certain offenses that, if merely alleged, place a child into the high risk category automatically without taking anything else into consideration. These offenses are known in Georgia as designated felonies. There are also more serious offenses known as SB440 (State Bill 440) offenses which, if alleged, automatically place the matter in the jurisdiction of the county’s superior (adult) court. We will discuss these offenses as well designated felonies in a further blog post.

Please contact us if you have any questions about the detention process for a child facing charges in juvenile court.